The year I turned seventeen, Mom’s car died and our rental house developed wall-cracks in which ants lived with criminal intent. Some ants were ruder and more deviant than others. Mom toxified our kitchen with ant motels and ant catacombs, but the ants continued to crowd our kitchen counters as if they were arriving at a jazz festival.

Mom had these daily rants about how crappy life in beautiful California was turning out to be. Even the peaceful hippies were getting her down. Some of them owned houses, she said, and drove better cars than us.

Our car was becoming famous for its dramatic ways of falling apart in scenic places. The possibility of our car’s demise was always playing like a sad old movie that we couldn’t turn off. And Mom’s jealousy of other people’s lives was beginning to feel like something that could swell up and eat us alive.

That year, snow scenes called to me from Christmas cards, promising to eliminate the pain. Our town was ecstatic about its new snow machine at the mall, and all I could think about was how I needed a machine to drive me there.

‘I hated driving in winter, but at least in Pennsylvania cars were reliable,’ Mom said.

When our car finally expired at Castle Rock State Park, the month after our AAA membership elapsed, I decided to lose my virginity. This felt like a tangible solution. Something I could do to help change my family’s bad karma.

At home, the car sat like an embarrassment in the driveway, watching me with its tomb of spiders’ nests and bird shit.

‘It’s dead,’ Mom said.

And so, I found myself visiting my former piano teacher. He was a vintage car collector, a middle-aged flake who enjoyed the company of his former female students. He used to call me “McPartland” when I studied with him, as if I were some kind of jazz sensation. I popped over, asking whether he could teach me how to drive. As predicted, he agreed immediately. But first, he said, he’d take me to see the snow in his bright green pleasure machine.

‘You’ll look like a million dollars in that green convertible,’ he said.

‘Snow, snow, snow,’ I sang, opening the convertible’s passenger-side door and sliding onto the white leather seats, warm from the sun. The top was down, and I couldn’t wait to feel the wind on my face and the sun in my hair.

I carried a giant handbag which my mother had gifted me and named “the behemoth”. Because it was so hefty, I cradled it like a child in my lap.

‘She’s my friend,’ I said by way of explanation when my piano teacher gave the behemoth a look intended for an uninvited guest.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘hopefully, she’ll enjoy the ride.’

When he started the convertible, the engine revved as if something was purring inside my body. Gosh, the vibration in the leather seat felt good, too good. I gave my piano teacher a look, wondering whether horsepower was foreplay to vintage car collectors.

Once we turned onto the freeway, the convertible suddenly picked up speed, and the behemoth lurched, almost falling off my lap. I caught her just in time, and my piano teacher reached out as if to brace me.

‘Careful,’ he whispered, with a wink.

‘I always am,’ I said. ‘The behemoth holds my life inside her.’

It was true. The behemoth contained everything I needed to survive my day: clean underwear , breakfast, lunch, snack, drinks, dinner, candy, condiments, lip gloss, tissues , vitamins, nail polish, nail file, mirror, toothbrush, hairbrush, wallet, pens, paper, sheet music, tuning fork, metronome, family photos, and a few sundries that shall remain nameless since a lady doesn’t speak of tampons. I call them tobaccoless white cigars. Apparently, my former piano teacher also didn’t speak of tampons or know what they were. I never imagined that an adult—even a single adult male bachelor—wouldn’t know what a tampon was. Boy, was I in for a surprise when he pointed down the behemoth’s wide-open mouth and asked, ‘What are those?’

The behemoth’s mouth was grinning at me, as if this were the funniest thing in the behemoth’s world.

I thought my piano teacher was joking, so I played it cool, not wanting him to think I was embarrassed. I said, ‘Those are my special white cigars. My lady cigars.’

‘Mind if I smoke one?’ he asked.

‘Why not?’ I handed him a tampon to see how far he would go. I thought he was joking, playing chicken with me, and, when he grabbed it from my pinched fingers, I didn’t want to be the one to flinch. ‘Shall I unwrap it for you?’ I asked.

‘That’d be great, since I’m driving. Got a light?’

‘Sure.’

I located a silver zippo deep inside the behemoth and, placing the insertable end of the tampon in my piano teacher’s mouth, I lit the string. It caught fire, and he started smoking the lit tampon while cruising down the freeway. Since the convertible’s top was down, we got some weird looks from rubber necks and almost caused a few accidents, but he didn’t seem to notice.

‘Tobaccoless? Very clever. Refreshing,’ he said.

‘Isn’t it?’ I asked, realizing then that maybe he wasn’t kidding, and that perhaps I had done something mean to him.

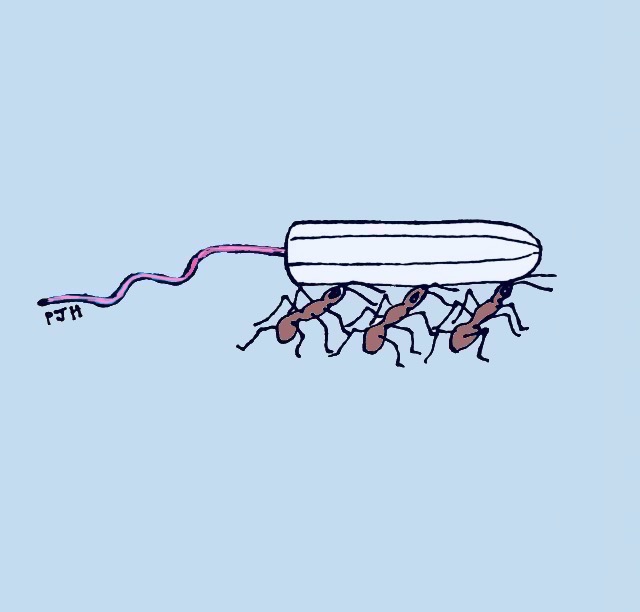

Gazing down into the behemoth’s gaping mouth, I was horrified to see hundreds, maybe even thousands, of ants eating my packed lunch. While my piano teacher savoured the “cigar”, I tried to distract him from the ants crawling out of the behemoth. With ants in my jeans, I thought it strange that I had been itching to lose my virginity, thinking maybe he would be the one. Now, watching him smoke my tampon, I was no longer sure he was the man for the job.

‘I like it,’ he said, ashing the tampon into the wind, then letting it go as it burned his fingers. ‘Oops. Maybe I’ll have another after we check out that snow machine?’

‘Sure – sounds great,’ I said, struggling to zip the behemoth’s ant-filled mouth.

Once zipped, the behemoth had a wicked smile, like maybe she loved riding in other people’s cars as much as she enjoyed eating ants.

Aimee Parkison is the author of five books. ‘Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman’ won FC2’s Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize. Parkison is Professor of English at Oklahoma State University and serves on FC2’s Board of Directors. More information about Parkison and her writing can be found at www.aimeeparkison.com

Meg Pokrass is the author of six flash fiction collections, and an award-winning collection of prose poetry. Her work has appeared in Electric Literature, Washington Square Review, McSweeney’s, and has been widely internationally anthologised. She is the co-editor of Best Microfiction.