In Which The Words of a Mother Hen Are Ignored by Her Less Noteworthy But Infinitely More Famous Son

Catching sight of her reflection in a trough one day, a talented Hen of Letters realised she was no spring chicken and if her literary genes were to be passed down to future generations, she had better take her beak out of her novella-in-flash and take appropriate measures. Besides, it would be reassuring to have about her youngsters to help out should she lose her reason or have a fall or become incontinent.

Our hen-chicken didn’t generally seek the companionship of stupid cocks, but she felt her offspring would benefit from being sired by a particularly resplendent – if dim-witted – specimen, whose gorgeous feathers and muscular body were the talk of polite fowl society. And, while the hen-chicken didn’t want her progeny to inherit the creature’s legendary ignorance or his regrettable indifference to The Arts, she reasoned that, what with the law of averages, regression to the mean and the odd recessive gene on her side, a union with the handsome beast would probably result in issue of at least average artistic sensibility.

And so, our hen-chicken set off to woo the cockerel, hoping, en passant, that her descendants would appreciate her great deed, for she certainly wasn’t expecting any personal gratification from her night of passion with the gorgeous specimen of poultry masculinity. Oh, no. She would much rather have been at the library, or playing Mah-Jong with the capon with bad breath across the road who could recite the whole of The Waste Land without recourse to notes.

(It so happens that, after the act, all the neighbours within earshot reported that the hen-chicken had in fact clearly enjoyed the encounter, but that is by-the-by.)

The courtship was swift, the cockerel being of a cooperative nature and willing to embrace any opportunity that presented itself without overly troubling himself about provenance. And thus it came to pass that the hen-chicken was blessed with a clutch of eggs which, one by one, hatched into fine healthy chicks with a passing appreciation of literature, even if none could exactly be said to be another Shakespeare.

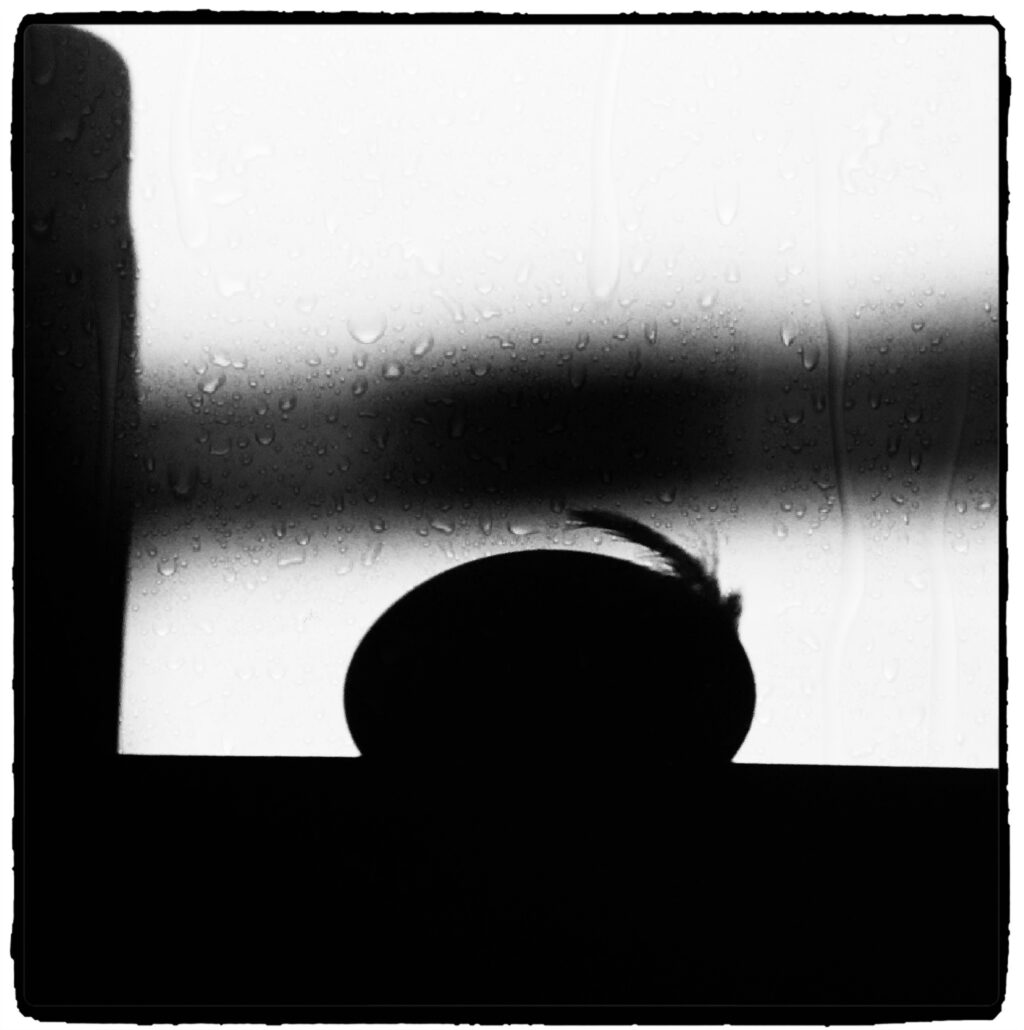

Soon, only one egg remained. It had a complexion suggestive of bone china, and the proportions of its girth to its height and of its height to the circumference of its neck gave universal delight. Graciously occupying the sunniest corner of the nest, it showed little inclination to eject a chick, but it had an aura about it, a touch of lazy aristocracy, a whiff of millennial entitlement, you might say, such that nobody felt it reasonable to oblige it to hatch within any specified timeframe. Furthermore, and most unusually for an egg, it grew two arms and two legs, and before long had learned to walk around elegantly and wave its arms in the air a bit.

News of the ovoid prodigy who walked around elegantly and could wave its arms in the air a bit soon reached the Royal Ear and, in due course, an emissary appeared before the hen-chicken to announce that His Majesty, attended by his entire cavalry, would be arriving on the morrow to witness the phenomenon.

Now, our hen-chicken was no royalist, but she gave the coop a good going-over with the hoover and spread copies of her chapbook, It’s Only Chickenshit If You’re Not a Chicken, into a hopeful fan shape on the coffee table. Early on the morrow she bade the egg do something useful with his arms and legs for once and scale the highest wall in the village and warn her when the King and his entourage appeared over the horizon, so she could put the kettle on.

She watched as he sauntered down the lane, managing to preserve the air of an Egg of Distinction even as he diminished into the distance. (Could it be that the creature’s noble carriage indicated some inkling of his impending immortality?) As he neared the bend in the lane that would obscure him from his mother’s view, some maternal instinct caused her to cluck:

‘Be careful, our Humpty!’

You will no doubt be aware of the price the egg paid for not heeding his mother’s words.

Somehow, the poor, grief-stricken hen found strength to complete several more liaisons with the handsome cockerel, but she never did produce an egg quite like her Humpty. And in the twilight of her years, she could oft be found perched on Humpty’s memorial bench overlooking the trough, chewing the end of her pencil as she drafted and re-drafted a moving epitaph to her late son (taking care, of course, to give due credit to the King’s men and horses for their efforts to save him). Little did she guess, though she was perhaps a tiny bit hopeful, that this tragic tribute would become her most significant contribution to The Western Canon, its influence echoing loudly – albeit mainly in nursery schools – down through the Ages.

S.A. Greene writes short fiction in Derbyshire. She dislikes walking in the Peak District. She has words in/forthcoming in Ellipsis Zine, Flash Flood ’21, Janus Literary, and Sledgehammer Lit. She has had words declined by too many prestigious literary journals to mention. Twitter: @SAGreene1.