Much has been written about trends in publishing, but less about the fate of books after they leave the store.

At the naff but harmless end of the scale, we organise books according to colour. Ours is a messy world and we have a thirst for order a la crayons. It is a display method that raises legitimate questions about the colour purple. Does it go with red or blue? A woman in Putney got so rattled about this question, she pushed her mauve ‘Atkins Diet’ behind the yellow section together with The Highway Code and a bottle of Johnnie Walker.

At one point everybody in London bought Capital because they lived in the capital and, in those days, there was a lot of capital around, although it was quite soon after the financial crisis and nobody could understand why there were still so many Aston Martins parked alongside the kerbs of Chelsea. The bookmarks from Daunt rarely made it past the middle.

From Richmond to Hackney, books sit untouched in piles, serving as extensions of bedside tables under glasses of filtered water and strips of Temazepam. In the evenings, their owners watch porn and Married at First Sight on their iPhones or scan Twitter to see what everybody else wants the world to think they’re reading. It’s been a while since John Grisham showed up in one of those curated stacks. You can’t be too careful these days. It’s hard to predict which will be the next wrong ‘un and, once you’ve put it out there, you can’t take it back.

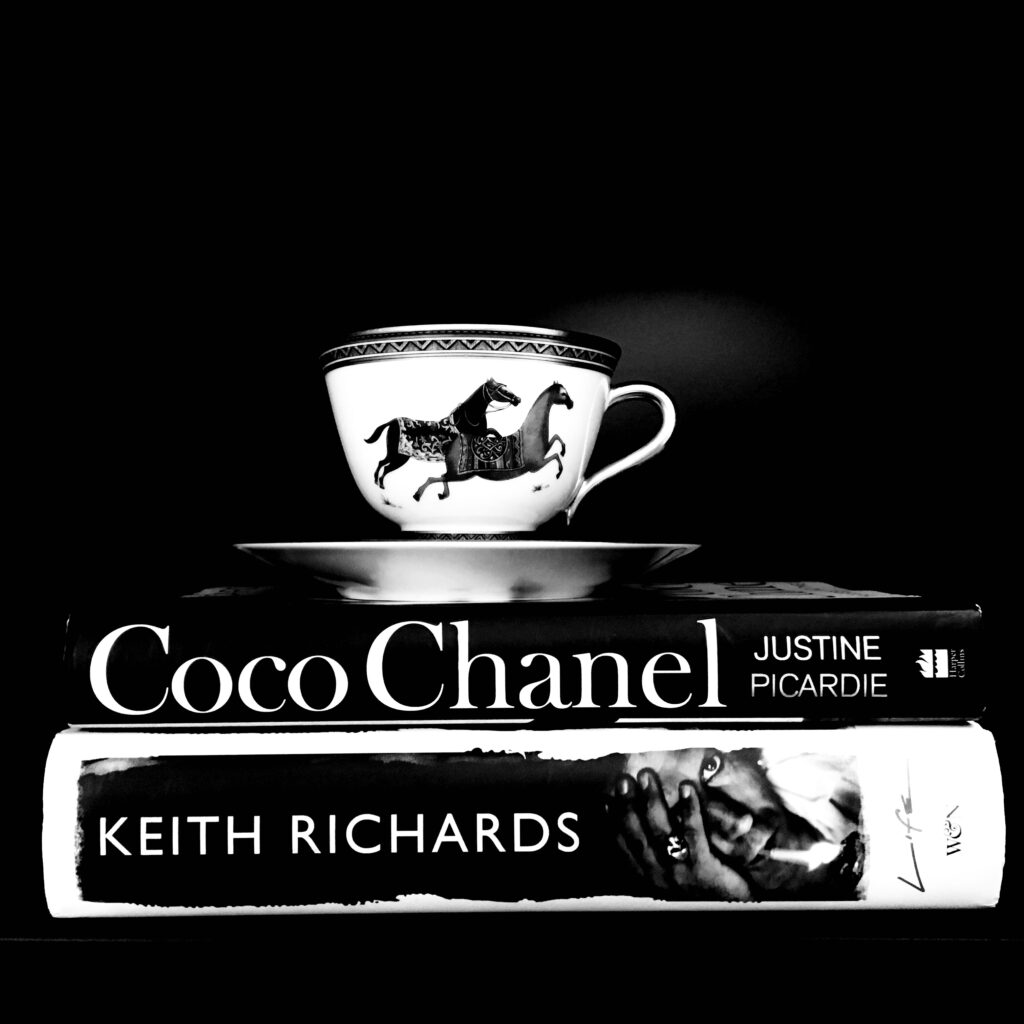

On the glass coffee table you can still get away with fashion if it’s the right kind which fashion makes sure it always is. Gardening is acceptable too. But be careful with art unless you want somebody to ask, ‘Yes, but is it art?’

There was a time when nakedness and cigarettes between lips, sometimes combined, was acceptable. Now? Not so much. Careful with biographies too in case there’s more to the subject’s past than you realised.

You can ease off a little when on holiday – there’s silent agreement that judgment is suspended on grass and sand. On trips to the Cotswolds or Tuscany, a Londoner may bring a pile of paperbacks, the mushy peas of publishing intended for nothing but reading. The paperbacks do not return to the city.

We wrap books in shiny paper and give them to those we wish to influence. A nudge tied in a ribbon may correct the recipient’s weight or steer them onto the right political path.

This can be tough on our young, but it’s the price that must be paid for preparing the little ones for dystopia. Anxiety is common and sleeping is borderline unethical anyway. Who do people think they are to leave the misery train for eight hours straight? The important thing is that we give our children the right message.

Except that some books insist on giving the wrong message. Now what? We aren’t in a position to ban, but we can damn right sign a petition if somebody dares to print words that should not be seen. We haven’t read them. We rarely read. But we know what we don’t like and we do not tolerate disobedience.

Despite our efforts, the wicked occasionally slip past the tastemakers and onto the bestseller lists. Soon, rage crosses oceans. Internet bonding sessions follow, warming the outraged hearts that the web itself has chilled.

In the night, rebels order ten copies of the offending book on Amazon, affronting the zeitgeist twice with one click, while sipping the last of the Malbec. But these nocturnal sinners may be hammering home a point they haven’t quite thought through.

Nobody speaks of the bonfire. But we all wonder. When it comes, will we have to burn the whole Kindle or is somebody going to invent something?

Ingrid Blakeney lives in London.