We are proud to present the winner of the Funny Pearls short story competition 2018

MEMENTOS

by Rebecca Kelly

The hedgehog had been dead for a week, its body unmoving beneath a scattering of late autumn leaves. Occasionally, a gust of wind would reshuffle its arboreal covering, revealing the tip of a nose or a quadrant of stiff hindquarters. But even so, for the first few days, I thought that it might be alive and that some strange, genetic mutation had compelled it to hibernate above ground and in the middle of the garden. My suspicions were finally aroused when, on the Sunday, it had become the interest of quite so many crows. I drew the curtains, paisley, but classic, and peered down onto the early frost of what was once your lawn and said a small prayer, not for the hedgehog but for you, George.

It is has been seven whole months and five days since you moved to that 1960’s bungalow in Littlehampton. It is a nice bungalow, if you like that kind of thing, although I find it hard to imagine that Joyce has contributed a great deal to its comfort and décor. I know this because I visit often and sit in my car across the road to watch your comings and goings. And in doing this, I have witnessed the dandelion yellow walls of the hall and the snatch of discoloured wallpaper in your living room and those dreadful curtains. Has she no shame? Poor you, George and, by the way, I love your new corduroys. How like you to choose my favourite colour when purchasing additional items for your wardrobe. Did you, like me, imagine how they will look hanging next to mine on the day we start our lives together? You must have bitterly resented your sudden flight to another location – one so distant from me and so far from civilisation and good taste. But Joyce knew by then, didn’t she? Knew that you and I were passionately, irresistibly in love.

You had been my neighbour for nearly a full year before it crept up on us. It was that day, last summer, the day your new wheelie bin was delivered by two women in shapeless overalls.

I waved over the fence and you waved back and I said, “Hello, I see you have a new bin.”

My comment had been both playful and somehow perceptive.

And you said, “Yes. All the mod cons.”

How we laughed.

You parked it by your garage, wheels squeaking a little as you pushed it along the path; then you wandered back inside and, if I remember rightly, there was a waft of something cooking in the air – something packaged and unwholesome. Did I hear the ping of a microwave and Joyce’s uncouth growl calling you in for lunch?

I returned to weeding the east border and it was at that moment that I was overcome, quite suddenly, with a vision – in every sense it was vivid and had the overwhelming character of a premonition. I knew immediately that it was a sign. In it, you and I were chatting across the chain-link fence, a trowel hanging loosely from your hand. And then you were leaning towards me, so close that the watery outline of your irises was evident in every detail, as was each hair of your manly brows. You moved closer and there was a slight smacking sound as your lips parted for a kiss. The vision ended there but the shock dropped me to my knees, weeds and earth falling from my fingers. What could I do but answer the call from your heart?

That moment marked the beginning of our love affair; it coloured everything that followed and a great deal that had fallen before: how had I missed the longing in your expression when we passed on the street or when you drove by in your car, Joyce’s loose neck falling baggily in profile beside you? Those friendly waves were now infused with all your pent-up desire.

And Joyce – how easy it was to understand that your loyalty had strayed – Joyce, with her triangular bottom, squashed into ill-fitting jeans and her lack of skill when it comes to the application of make-up. And those teeth – teeth that belong to another animal – one that could surely not be human. Sometimes I imagined your mornings, waking to those exposed edifices of yellowing enamel, a necklace of morning spit hanging from their tips – and shuddered for you. You endured it all – the microwave dinners and packet cakes, sounds of a vacuum no more than twice a week and her dreadful taste in interior design. How I, so laden with earthly gifts and classic finesse, must have fed your fantasies.

From that moment I took even more care with my hair and dresses – classic – and if my stilettos were sometimes a hindrance to effective gardening, I endured it all for your sake. I made every effort to cross paths, ensuring that we met at least once on your Saturday walk to the newsagents. I had heard your psychic plea, George, and I took every opportunity to answer it. “How are you?” I would call over the wall as you left for the bowls club, but Joyce must already have been on to us because sometimes your answer was so brief that I knew she must be watching from behind those badly chosen drapes.

It became clear, about three months after that first vision, that if we were to be together, I would have to be the one to take action, so I began to call you. Unfortunately, Joyce generally answered and, on the only occasion you actually picked up the receiver, I dropped mine in shock. So I began to ring in code – two buzzes and then I would hit the off button and, just to be sure you understood, I posted that card with the number ‘two’ on it through your letterbox.

Every evening, even in the rain, I would sit in the garden, late into the night and gaze up at your bedroom window, a sort of romantic ‘bonsoir’, although at some point Joyce decamped you both to another room at the front of the house. Would she stop at nothing?

So I began the letters. These, I tried to keep as interesting and varied as I could – sometimes it would be a poem, Shakespeare or Rossetti, at others times I would include a recipe for the sort of cake I might cook when we were finally together. Often it was a series of my own random thoughts or an essay outlining my political reflections on Brexit and Trump. I am not a boring person, George. I have class.

In July, your agony must have become overwhelming because you eventually phoned back, but Joyce surprised you – how like her – and when I announced myself, you muttered, “Wrong number,” and replaced the handset. But I knew it was you and I knew that it was a final and anguished cry for help. Joyce was clearly digging her nails into you with even more possessive ferocity than before. After this, I started waiting for Joyce to answer and then I began to tell her exactly what I thought of her – until she changed the number.

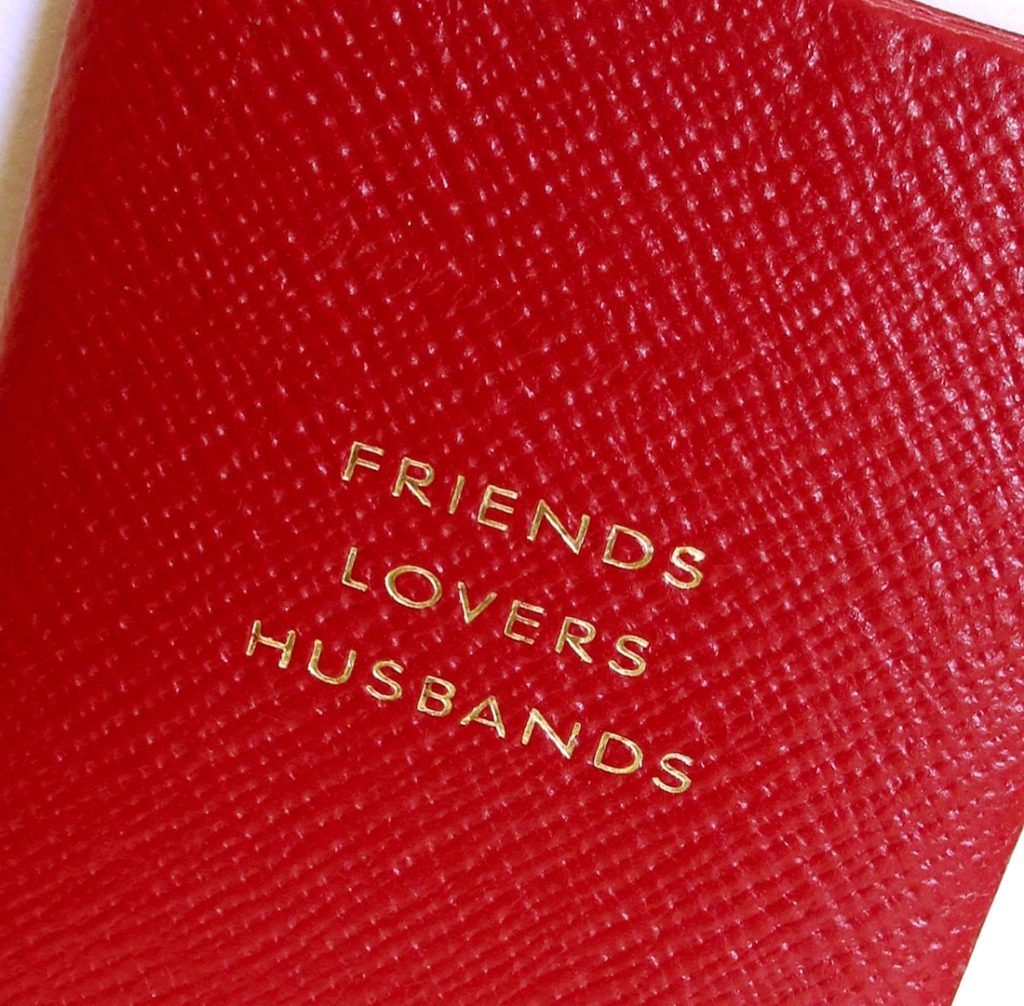

It was at this point that stronger action was required and I began posting the mementos: a picture of a wheelie bin, a weed from the east border, a pebble chosen from outside the newsagents and a page from the telephone directory. The more I thought about them, the more mementos there seemed to be. And, giving me the courage to carry on, were the dreams and visions which arrived now nearly every day and dominated my nights.

Anyway, this morning I had a shock, and if I am honest, I am still unsettled. I was in the kitchen and surveying the hedgehog which now, in the final stages of decomposition, could not be denied its fateful demise, when the doorbell rang. I composed myself as best I could although my heart clattered in my ribcage. It had to be you, George, at last escaped from Joyce’s malign clutches. How long had I prepared for this very moment? Clearing out half the wardrobe to accommodate your clothes, buying pyjamas and bathroom accessories ready for your arrival. And in frames, on every wall of the house, were mementos that would speak to us of our great love until the very day that death became the final resting place.

But it was not you on the doorstep. It was, in fact, the postman, the one with what looks like a small mammal glued to his chin. After my initial disappointment my hopes soared, because surely the postman was bringing something from you, some token of your affection? But when he pushed the parcel into my arms, the shape was suddenly and horribly recognisable as the one I last sent to you in Littlehampton – the one containing a loaf’s worth of granary breadcrumbs and half a mince pie. A message that only you would understand.

“No, no,” I said and tried to explain that this was meant for you, George.

“Sorry, love,” the postman shook his head, “They must’ve moved,” and he pointed to the scrawl: ‘not known at this address’.

“But where are they?” My throat burned with a sort of uncontrollable rage.

Where had you gone? Where had she taken you? But the postman shrugged and told me that he simply didn’t know.

It is nearly three now, and the sky is a winter white and frost is beginning to web the dying grasses with filigree perfection. Anger grips my insides, but I remind myself that I am stronger than Joyce and that our love will rise above her petty and desperate machinations. So earlier, I put on a pair of red kitten heels and went to investigate the hedgehog, mined now by scavengers – bugs crawling like a trickle of syrup onto the sodden earth. I pulled on a pair of disposable gloves, rolled the body into a carrier bag and brought it inside. And, even as I speak, I am attempting to fit the hedgehog into packaging.

Tomorrow, I will travel to Littlehampton and to your last address. Once there, I will do whatever it takes to discover your new location. Anything. For a moment, I close my eyes and send that promise through the ether to your eager and listening ear and I hear your answer. I have been too soft in the past, I can see that now, but when I find you again – and I will – nothing and nobody will keep us apart. Not this time, my dearest.

Rebecca has always loved words and has written in one form or another nearly all of her life. She is the winner of the 2018 Exeter Novel Prize and is currently working on her second book.