Lying on a gurney as I exited the operating room, still wearing my paper underwear, it occurred to me that I should outwardly acknowledge my experience with the staff. ‘Thanks, it was good’ or ‘Thanks, I had a good time’ entered my mind. Neither felt like the appropriate parting salutations to describe what it is like to be a fully awake, non-medicated patient who goes through surgery, and now wants to say something appropriate on the way out.

The day had started at eight in the morning at a busy, downtown Toronto corner. I’d been dropped off with my travel mug in hand to walk to my procedure. A wire, not dissimilar to a fishing line, needed to be inserted into my left breast beside my nipple. The wire allows the surgeon to know exactly where the offending lump is.

After the insertion, my breast was squished into a depth finder, with the wire in tow for imaging. I checked my phone for four hours until it was time for the surgeon to troll inside my breast using the wire as a guide. After three hours, the earlier lidocaine freezing began to wear off and I became aware of a new sensation in my breast, like what I imagined a nipple piercing would feel like in the first twenty-four hours.

When it was time for action, I moved from tiny room to tiny room with hanging sheets posing as curtains to separate me from other patients. In each location, I politely corrected staff whenever they referred to my surgery by letting them know that what I was having was a “procedure.” I preferred this term seeing as procedures aren’t serious and don’t require sedation or anesthesia. My husband had a vasectomy and it was called a “procedure”. He did choose to pop an Ativan beforehand, and then walked out with an ice pack firmly between his legs. That was the plan for my procedure today too, minus the ice pack and the Ativan. Add one post-opioid, please.

By the time I arrived at pre-op, in place of my own bagged-up and labeled belongings, I had acquired a bag of saline to carry around attached to an IV. I was told that my stuff would be waiting for me at the end, like luggage at the airport, only this journey didn’t allow me to leave the hospital and would require me to give up a physical part of myself. As I walked to the washroom with my D cup bag of saline held high, I thought about my breasts. In the privacy of the latrine, I imagined what my boobs would feel like filled with smooth saline implants instead of the lumpy ones I had.

The next area was V.I.P. Unlike everywhere else it was comfortable, with reclining armchairs, heated blankets and a large, looming crucifix on the wall by the nurses’ station. I coined this place, “the last stop before take off”. In the presence of my surgeon, I signed a form that I didn’t read. Afterwards, an anesthesiologist came to speak to me. She asked about my weight, yet again, which is a hard thing to pin down when you don’t own a scale. Could be 140 pounds. Could be 150, considering Covid weight. Seeing as they did not seem to have a scale at this hospital, I fancied the thought of hiring a carnival worker to guess my weight for ten dollars. In my experience, they’ve always been accurate and it would have been an entertaining distraction.

The anesthesiologist moved on to the topic of sedation and then, for fun, I asked what the available menu options were. Why ask me last minute? How many options are available to me and why weren’t they presented to me a week ago? It said in my personal file, which I saw her holding, that I had chosen no sedation. She wasn’t very forthcoming,

Without a fancy anesthesia menu at my disposal, I reiterated my decision not to have anything other than lidocaine. The anesthesiologist was already miffed about the teaspoon of milk I’d had in my coffee three hours earlier. In response, I informed her that the intake woman who called two weeks ago said I could have coffee. (She also said she would pray for me). Ten minutes later, I overheard her complaining about my milk consumption to someone and I closed my eyes to relax and set my caffeinated mind at ease.

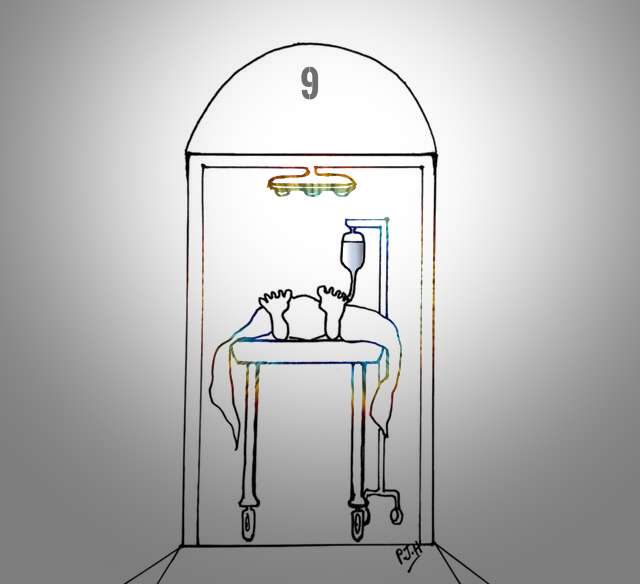

Operating Room Nine was next on the schedule. With my bag of saline in tow, I walked to surgery behind a staff member in a paper-yellow ensemble. As I turned the corner into the operating room hallway, I saw what unexpectedly brought me back to my childhood visits to family farms. There were what looked like cattle water troughs lining one long hallway. On the opposite wall of the metal troughs were windowed double doors leading into numbered surgery rooms. Through the windows, I saw hanging limbs pointing awkwardly in different directions, as people in paper scrubs opened or closed the appendages as required. My eyes reverted to the animal troughs and then to the unidentified appendages accompanied by hovering humans. I was next, in Room Nine.

Thankfully, I was not assigned Operating Room Thirteen. It exists. Apparently, society is more superstitious about failing elevators than botched surgeries. I was informed by a nurse that Italians often request the thirteenth surgery room. Good to know that, like snacks at school, I could make surgery room switches with Italians.

In the surgery room I offered my hellos to everyone, including my surgeon. I hopped on to the surgery table and they began right away by strapping down my limbs. Gone were any chances of readjusting the complimentary paper undergarment or nervously scratching my face. I was layered up with a multitude of thin paper sheets of varying sizes, including one that was partially draped over my face. The anesthesiologist uncovered my eyes — a silent gesture of human kindness.

The surgeon injected lidocaine into my breast tissue and I let them know that I always need extra at the dentist. Shortly afterwards they pushed down on my skin. It hurt. They gave me more lidocaine. I felt prodding. He inserted more and then, with a lecturing tone in his voice, asked someone, ‘How much lidocaine is toxic?’ I panicked. Again, they inquired about my favorite topic – my weight. This time my answer seemed more relevant. Where was that carnival act when I really needed it? Surely, they would be paid better working here than at the annual fair? I was informed that the quantity of lidocaine the team were using came in just under toxic and while I still felt some poking and pulling, I considered my options: toxicity or pain. I chose the latter. The anaesthesiologist asked a few chatty, non-medical questions. I requested that she stop talking to me as I needed to stay in “the zone.” I did not see her again.

At one point my left leg began to quiver. I informed the team of this new development. From behind me, I heard a male voice ask, ‘What if she seizes?’ I lay there wondering why he would ask that, and what it would feel like if I did seize. With deep breaths, I forced calm energy into and down my leg, and within minutes it stopped shaking. I heard the comings and goings of the staff like background noise at a party. And like at a party, when someone laughs too loudly or falls down drunk and breaks the rhythm of the room, I too broke the flow in Operating Room Nine when I felt a yank and a hard pluck. The surgeon had jerked the line and was reeling it in. I spontaneously yelled, ‘Fuck!’ There was a silence and then I apologised for my outburst. The surgeon made light of it by saying, ‘God doesn’t like that in this hospital.’ Awkward silence. Then laughter from everyone, but me.

Next came the ultimate exercise in disassociation. I asked what the new sound was accompanying the sensation I was feeling. My surgeon said he was cauterizing the area. Burning the inside of my body. My leg started trembling again. I didn’t tell anyone this time.

When my procedure came to an end, the surgeon left the room. I asked why he was leaving and was told that my lump was being x-rayed to make sure that they had taken out the right spot and extracted all of it. The nurse started to sew me up. ‘Shouldn’t you wait to stitch me until he returns?’ I inquired.

‘Nope, it’s easy to pull out the stitches if we need to go back in,’ she replied.

I knew right then that, if anyone was going on another expedition through my breast, I would be calling back my chatty new acquaintance from earlier. Luckily, the surgeon quickly returned and announced that everything ‘was good’.

Bandaging complete, they unbuckled me. I sat up and swung my legs around to leave the way I had come in – walking.

‘Oh, no, no,’ someone said, and I felt gentle hands guiding me back onto the gurney to be rolled out.

‘Thank you,’ I said to the surgeon. ‘It was…something.’

And then I was gone, joining the mass of people in recovery.

Michelle is a teacher, who enjoys writing plays and first person essays in her free time.

Michelle is a teacher, who enjoys writing plays and first person essays in her free time.