Florence Alexander was an average writer widely rejected by London’s literary agents, most of whom had received at least one of her manuscripts, accompanied by a lavender-scented, stamped, addressed envelope. Undeterred, Florence persisted until one day a young reader mistakenly stapled his orange Post-It note to the official rejection letter. ‘This is the dullest three thousand words of drivel I ever read,’ he had scribbled next to his sketch of a matchstick man hanging from a noose.

Whilst this stopped Florence from submitting her manuscripts, it didn’t deter her from writing. It couldn’t. Florence wrote out of need rather than conscious desire, increasingly under different pseudonyms. She filled drawers, notebooks and hard disks with novels, screenplays, poetry and short stories inspired by her early life in a Cotswold village.

Florence was an only child whose parents had miscommunicated with each other by means of sulking, shouting and giving each other the silent treatment. From a young age, Florence had done her best to avoid them both. Books had been her refuge – first reading them, later writing them. Nestled in corners of the garden, attic and her neighbour’s courtyard, which she accessed through a hole in the hedge, Florence wrote stories about people who were nice to each other. She was rescued aged eighteen, when a childless aunt left her an apartment near Sloane Square. Years later, with a teaching degree to her name, she was offered a job at a local prep school where she was to teach the international children of the wealthy. This environment suited Florence because nobody there asked awkward questions about how a teacher afforded a four-bedroom apartment in Cadogan Gardens.

Like most people, whether they acknowledge it or not, Florence came to lead a life dominated by routine. Every morning she took breakfast in her conservatory whilst reading the paper version of The Times. At eight she was at school and at five she walked to Partridges, a pricy food shop in The King’s Road where she bought her supper, a green salad with a slice of smoked salmon. She ate her meal whilst watching the London news on BBC One. Afterwards, she made espresso, settled in her study, which overlooked the garden square, and typed on her shiny Mac until eleven thirty.

On a Tuesday she hosted book club night for a group of local women, on Friday evenings she attended swim class in the public pool in Chelsea, and most Sunday afternoons she exchanged platitudes with her widowed mother over the phone.

‘My parents never knew me,’ Florence would say to the very few friends with whom she discussed her personal life, ‘they were too busy hating each other to take any notice.’

It was a statement made with sadness yet free from bitterness. Florence knew she was lucky in many ways and was contented with the life she had been able to create with a little help from her aunt. Hers was a stable and peaceful existence.

It remained so until one sunny autumn day, when an otherwise nice enough doctor at The Lister Hospital by the Thames found something on one of Florence’s ovaries that should not be there.

Florence spent four days in terror, not – as one might expect – at the prospect of a short-ish life (she was forty-nine), but over the cold realisation that she hadn’t done much with hers.

‘I need to leave my mark on this world’, she thought as she sat in her study watching a squirrel race up and down the oak tree in the communal garden. She knew what sort of mark she would like to leave – her name on the shelves in libraries and bookshops – but the agent’s note loomed large, and Florence had no illusions.

‘It’s all about the hype,’ Carla from book club often said, ‘these days it’s all about the hype.’

Not that Carla knew of the tens of thousands of pages hidden away in Florence’s study, it was a general comment, most recently made with reference to a blockbuster the book club had hated. But Florence took comfort from her words nonetheless.

When the gynaecologist rang with the message that she would need an operation but otherwise was likely to be fine, Florence fell on her knees telling God she would never ask for anything again. But the notion of leaving a legacy had taken hold, and Florence’s brain remained in hard thinking mode.

‘It’s all about the hype.’

It wasn’t that she agreed with Carla entirely. Florence thought good books would create their own hype whereas average books probably needed a boost. But how does one create hype out of nowhere? It seemed to Florence that hype was a self-perpetuating entity; something big was made bigger because it was already big.

She considered this as she walked along the King’s Road, heading towards Waterstones book shop to spend the hundred pounds worth of vouchers given to her by the book club for ‘recuperation reading.’ Their gesture had brought tears to Florence’s eyes.

She entered the store, vouchers crisp in her pink Ted Baker wallet, her eyes scanning the books laid out on low tables.

There must be a fashion for elaborate colours this year, she thought as she watched customers pick up hardbacks, studying jackets with serious author photos that said this person is somebody who knows life.

There were giants on those dark, wooden tables. People who could string sentences together to make readers blush, cry, long, dream and feel understood. As far as Florence was concerned, the authors deserved all the fame in the world, all the money in the world and all the gratitude in the world.

There were popular storytellers, people who made you lose sleep because you were yearning to see what would happen next. People who made you cheat and look at the last page because you were scared something might happen to you between now and the end-point and that you might never know.

Many of those treasures had been reviewed positively in The Sunday Times and it was exciting to see them all in real life. What unsettled Florence was the fact that they were so obviously competing for attention: having to suffer the indignity of being picked up and fondled by people with raised eyebrows and dirty hands, most of the time only to be put down again. Back on top of another superstar on a background of dark wood.

These were the people who had managed to get a literary agent, then a publishing deal, followed by the attention of reviewers, journalists and book clubs. And after all that, they still ended up at the mercy of strangers. Even ‘My Tits in the Cup Cake’, a recent work by a young blogger with a YouTube channel and a million followers. Hype in spades but still competing for attention on a table.

Half an hour later, Florence found herself back on the pavement, overwhelmed and bookless, vouchers intact in her wallet. As she stood there amongst a crowd of tourists on the King’s Road, God, or somebody, planted in Florence an idea she thought so brilliant that she followed the tourists trail into the gelato parlour and bought a cone with three scoops.

Back at her flat, she printed the list that the hospital had emailed and packed her items accordingly whilst drinking a thin gin and tonic before eight, (she was required to arrive at the hospital on an empty stomach). Afterwards, she spent an hour or so looking for a suitable manuscript. She decided on ‘Summer in Stow-on-the-Wold’ by one Torance Daylingale, the story of Eliza, a quiet woman, aged around the fifty-mark, who meets and falls in love with the man she dated briefly when she was seventeen. A man who, when they meet again, is as handsome as ever and tells Eliza that he has never forgotten her. A fair amount of sex follows (scenes Florence had needed extra gin in her tonic to write). About two-thirds into the story, conflict arises when the lover’s adult children struggle to accept their father’s new relationship. In the end, all is resolved and Eliza marries her hero in a floral display somewhere in The Cotswolds.

It would be easy to come up with suitable cover for that one, thought Florence. An image of a stone cottage in a lavender field with the title in a classy font such as Modern 20 or similar.

The following day, she checked into the hospital in an elevated mood, impressing the doctors and nurses with her positive attitude. She was pleased with her accommodation, a nice, air-conditioned room with a private bathroom and a view of the Marylebone Road. A safe, urban environment.

She got through the operation without problems, slept twenty-four hours afterwards, and woke up in slight discomfort with a craving for Beef Wellington. She spent the next few days lying down marking her manuscript with a red pencil. A selected group of her pupils came to visit with Mrs Lectern, the headmistress, bringing Fortnum and Mason tea and chocolates. Florence was touched, yet distracted.

At home, Florence recovered quickly, and once back on form, she chose a lovely photograph of a lavender field from her iPhone photo album and emailed it to reputable printers in Tunbridge Wells together with her manuscript and a cheque.

Four weeks later she took delivery of sixty hardcover copies of ‘Summer in Stow-on-the-Wold,’ by Torance Daylingale.

Nervous and wary of security cameras, she tied a pink scarf around her head and set off on her mission.

She began appropriately in Waterstones on the King’s Road, squeezing two books onto the shelf under D. She then continued to Kensington, Chiswick, Piccadilly and Hammersmith, leaving one book in each store.

Over the next two weeks, she travelled to Waterstones branches around London, squeezing one or two books onto the crowded shelves.

‘I am a published author whose books are on the shelves of reputable bookstores in Central London,’ she giggled to herself, toasting in a delicious glass of chilled Cabernet Sauvignon.

Three weeks later, a Swedish tourist by the name Annalisa Andersson was waiting at the till in Waterstones Piccadilly whilst Igor, the friendly young shop assistant, ran ‘A Summer in Stow-on-the-Wold’ through the scanner. Or rather attempted to do so.

‘It doesn’t seem to have a bar code,’ said Igor, holding up the book staring at it from all angles.

Annalisa didn’t care about bar codes. She just wanted to pay for her book.

‘Let me make a phone call, and I’ll find the price for you,’ said Igor.

Weeks went by, phone calls were made, emails sent, heads scratched and CCTV footage studied.

But one Wednesday evening when Florence was picking stubborn clingfilm off her salad in front of the television, she broke into a smile when the presenter held up her novel with the lavender field cover, telling viewers how identical books had been found around Waterstones stores in town, fifty-nine in all. The presenter proceeded to interview Igor and somebody from a publishing house about the mysterious Torance Daylingale.

‘It sounds like a pseudonym, don’t you think?’ asked the presenter, pulling her best quantum physicist expression.

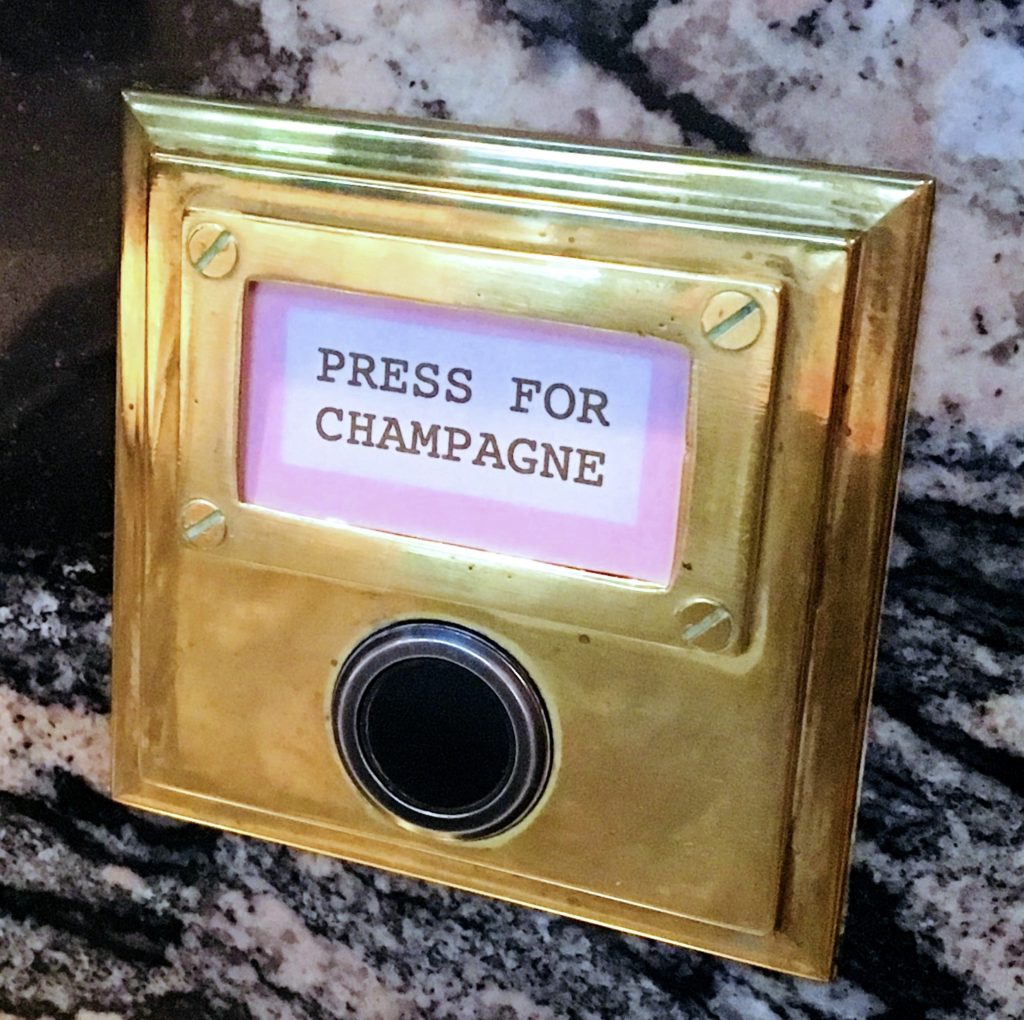

Florence opened a bottle of Veuve Clicquot.

The following evening the presenter spoke directly to the camera.

‘Torance, do listen if you’re out there. After our segment last night, Waterstones have been inundated with orders for your book, but nobody knows how go to about it until they can speak to you. So, Torance, or whatever your name is, do get in touch. You’re about to become a very successful author.’

‘It’s all about the hype’, thought Florence.

She would wait a few more days.

The phone rang and for a moment Florence thought they had found her. Maybe through an algorithm.

But it was Clara from book club.

‘It’s you isn’t it, Florence?’

‘Of course, it’s me.’

‘No, I mean Torance Daylingale. It’s you isn’t it?’

‘It’s me,’ said Florence.

Rebecca Taylor is a regular contributor to Funnypearls.com